FTN Roadshow Blog Series* – Improvisation

by Melissa Meade, Colby-Sawyer College and Cricket Keating, Ohio State University

Comedian Tina Fey has recently foregrounded two key tenets of successful improvisation. The first she dubs the “Rule of Agreement.” In her words, “the Rule of Agreement reminds you to “respect what your partner has created” and to at least start from an open-minded place. Start with a YES and see where that takes you” (Fey 2011). The second rule is that in addition to saying yes, you should add something of your own; that is, you should say “YES, AND.”

As an experiment in learning, the FemTechNet DOCC has been marked by an improvisational ethos. Indeed, from its open-ended organizational structure, which encourages educators of all sorts to join the collective, to its open-ended network of classes, to its key learning projects distributed across the network (such as Feminist Wiki-storming, Situated Knowledges Map, and Exquisite Engendering), FemTechNetters have said again and again “yes, and.”

In adding our “yes, ands” to the improvisation, we partnered the undergraduate students at Colby-Sawyer College (a private, liberal arts college of about 1400 students in central New Hampshire) and the Ohio State University (a large state university in central Ohio with about 44,000 undergraduates on a campus with about 58,000 students).

As instructors coming out of media and cultural history and political and feminist theory, neither of us particularly professionalized or skilled in digital media production, we joined this shared teaching and thinking project with a “DIY” mantra firmly in mind: a do-it-yourself feminist politics that suggests we ought not wait to be invited into circuits, but that we jump in and add our own.

As critical inspiration, we read Riot Grrrls and feminist DIY punk cultural production of the 1990s in our classes. They said, “Because we must take over the means of production in order to create our own moanings.” Yes, and we say “FemTechNet is a power tool” (FemTechNet Manifesto).

Animating a DIY approach with an improvisational spirit to us underscored that DIY is actually a misnomer. We need others — we need each other — to do the kind of work that will upend hierarchies, eliminate violence, create room for difference in the academy and beyond, and move past individual expressions of identity, the isolated and isolating digital practices. And so began our move from DIY to DWO (doing with others).

Much has been made of the role of the amateur in digital economies. Some have heralded its presence as a liberating creative spirit, with the ability to elide expertise and professionalism directly correlated to increased participation in the marketplace of ideas (see, for example, Lawrence Lessig and Clay Shirky). Carolyn Marvin has also critiqued the rise of the professional engineer and scientist of old technologies as tied to the exclusion of women and minorities in these fields (Marvin 1988). By squashing the tinkering impulse, and the tinkerer, we reinscribe hierarchies of thought, labor, and power.

Others have noted that amateurism is too easily coopted into the logic of neoliberal economies. DIY becomes a brand, and the amateur becomes a creative psychology useful to a growing economy. Astra Taylor has noted that “the grassroots rhetoric of networked amateurism has been harnessed to corporate strategy, continuing a nefarious tradition” and warns, “When we uphold amateur creativity, we are not necessarily resolving the deeper problems of entrenched privilege or the irresistible imperative of profit” (Taylor 2014, 63- 64).

Marshall McLuhan once intoned that “the amateur can afford to lose.” Yes, and we say: “Irony, comedy, making a mess, and gravitas are feminist technologies” (FemTechNet Manifesto).

In addition to jumping into the projects already in place in the network, we added some of our own, and invited others to join us. Inspired by the Object Making key learning project, and wanting to render visible what are often invisible gendered technologies, the Colby-Sawyer students developed a Bra Project that would be showcased at a Fem Fair. Inviting others to join us in this improvisation, we put out a “Call for “Bras” across FemTechNet. Here the network said yes, and sent dozens of bras, bindings and underthings through the mail. The students decorated, mutilated, and repurposed these into visual displays of gendered technologies. The Fem Fair took place in rural New Hampshire, while capturing the spirit of the dispersed and distributed FemTechNet.

Celebrating “The Bra Project” at Colby-Sawyer College, Fall 2013

Celebrating “The Bra Project” at Colby-Sawyer College, Fall 2013

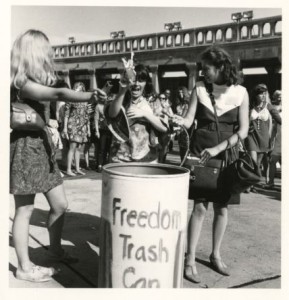

At Ohio State, our class developed the idea of Freedom Recycling Bins. Taking inspiration from the “freedom trash cans” of the feminist protests at the 1968 Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, we repurposed trash cans so that they could be used as depositories of objects that symbolized or that perpetuated oppression. We then brainstormed how each object could be recycled and repurposed to serve liberatory ends. Later, we developed a game based on the idea. Here’s how to play!

Freedom Recycling Bin: The Game

Players: Unlimited

To play, you will need:

A trash can

Markers, paper, playdough and other repurposing supplies

A timer

How to play:

- Label a trash can a “freedom recycling bin” and put it in the middle of the room.

- Set the timer for five minutes. In that time, each person places an object that represents or perpetuates some aspect of oppression in their lives (either the actual object or a representation of the object) into the recycling bin.

- Break up into even-numbered teams.

- Set a timer for 10 minutes. Racing against the clock, each team picks an object from the recycling bin and repurposes it for liberatory ends. Keep going until all the objects in the recycling bin are repurposed or until the time runs out.

- Groups share their repurposed objects with the others. The team with the most successfully repurposed objects wins the round.

- Repeat as often as necessary.

Speaking of the imperative of coalition work, Bernice Johnson Reagon writes: “we have lived through a period where there have been things like railroads and telephones, and radios, TVs, and airplanes, and cars and transistors, and computers. And what this has done to the concept of human society, and human life is, to a large extent… what we have been trying to grapple with” (Reagon 2000, 365).

Reagon stresses that a consequence of these technological transformations is our vulnerability– “there is no hiding place”– and our connection– we have to build coalitions through and across difference in order to survive (Reagon, 365). Yes, and we say animating these coalitions, both on and off-line, with an improvisational spirit will help us to deepen, expand, and multiply them. There won’t be a place oppression can hide.

References Cited:

FemTechNet. “Manifesto.” Femtechnet.org, 2014.

Fey, Tina. Bossypants. Little, Brown and Company, 2011.

Marvin, Carolyn. When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking about Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 1988.

McLuhan, Marshall and Quentin Fiore. The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. Bantam Books, 1967.

Freedom Trash Can Photo: https://mediamythalert.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/bra-burning_freedomtrashcan.jpg

Reagon, Bernice Johnson. “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century,” Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, Barbara Smith, ed. ([Kitchen Table Press, 1983] Rutgers University Press, 2000.

“Riot Grrrl Manifesto,” Bikini Kill Zine 2, 1991.

Taylor, Astra. The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age. Metropolitan Books, 2014.

*FemTechNet Roadshow Blog Series – Over the past couple of months, about a dozen FemTechNet participants have presented work based on our research and teaching related to FemTechNet in a two-part FemTechNet Keywords Workshop at the CUNY Feminist Pedagogies Conference in April 2015, and at the Union for Democratic Communications Conference at the University of Toronto in May 2015. Since these gatherings brought together such divergent modes of FemTechNet engagement, we thought we’d collect and share this new work over the last two weeks of May, leading up to the deadline for our 2015 FTN Summer Workshop. For more information on this series, contact T.L. Cowan